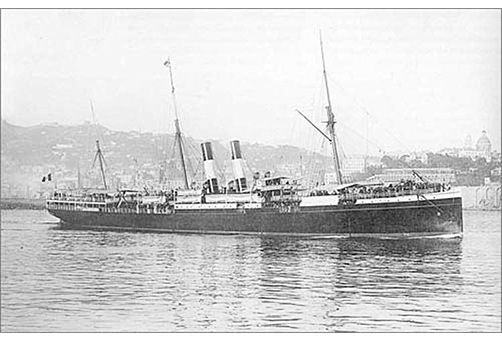

Owned by the company Navigazione Generale Italiana (NGI), it was one of the ocean liners that sailed from Genoa to the New World in its day. It was the early 20th century, and millions of people were leaving Europe, fleeing poverty and hunger to seek the dream of a better life on the other side of the sea.

The Sirio holds the dubious honor of being the most significant civilian shipwreck in the Mediterranean. Six years later, the tragedy of the Titanic would eclipse the Italian steamship, but unlike the Titanic, the exact number of deaths on the Sirio was never known because the exact number of passengers on board was never known. Today, the figures still range from the 242 declared by the insurance company to the 500 estimated by the press at the time.

On August 2, 1906, the Sirio set sail from the port of Genoa. The next day, it stopped in Barcelona, where more people boarded, and continued on its way to the Atlantic. Off the coast of the Hormigas Islands, as eyewitnesses and even the third officer on board, Tarantino, who reported this to the captain, would later note, the ship was sailing too close to the coast at a speed of 15 knots through an area of shoals that was marked on all nautical charts. Captain Giusseppe Piccone ignored the warning.

On August 4, 1906, it struck the head of Bajo de Fuera, a 200-meter-long rock with only 3.6 meters of water above it, becoming the largest civil shipping accident on the Spanish coast in the 20th century. The impact was heard from the coast. The ship, mortally wounded, ran aground on top of the shoal, with its bow raised, and listed to starboard.

The leak began to flood the aft compartments. The boilers exploded, spreading death, and the alarm siren sounded like an agonizing scream. Panic spread throughout the ship. The starboard boats were submerged and those on the port side hung from their davits inside the ship, rendering them useless.

There were not enough life jackets or life preservers. On deck, passengers were trapped under the awnings that protected them from the sun, and there was no one to turn to for guidance, as the crew had hurriedly abandoned ship in one of the first boats. The passengers, in a state of panic, fought fiercely for anything that would allow them to float, and began to throw themselves into the sea.

Just three miles away, in Cabo de Palos, vacationers, fishermen, and sailors watched in amazement at what had happened. According to Juan de la Cierva, former Minister of the Interior and a regular summer visitor to the village, while Cartagena was being notified by telephone, smaller boats rowed to the scene of the accident. Vicente Buigues, who was returning from fishing with his cousin Bautista, was perhaps the closest.

He set course for the Sirio and lowered a first boat, which capsized in front of the crowd of people who tried to board it. He then opted for a risky move: to approach the Sirio with the bow of the Joven Miguel so that the shipwrecked sailors could pass through the bowsprit and get to safety aboard their own ship.

The spontaneous action of the fishermen of Cabo de Palos (in contrast to the inaction of the crew of the ocean liner and the large ships in the area, such as the Marie Louise and the Poitou) prevented a greater tragedy, saving more than 400 lives.

During the official investigation carried out in Italy, a reason was found for the inexplicable defeat: the ship was engaged in the clandestine trafficking of migrants. “This explained why the ship recklessly approached the coast in an attempt to make up for the time and fuel lost in clandestine pickups, or to take on a new load of migrants.”

The Sirio remained on the surface until the 13th, when the lookout boat heard the sound of the hull breaking in two. The bow remained stuck between the rocks for another week before also sinking to the bottom of the sea and disappearing forever from the horizon of Cabo de Palos.

Numerous species swim among the bow with its characteristic railing, which rests on its side on the south side at a depth of 50 m. The stern and its boilers, covered with beautiful gorgonians, are located to the north, at a depth of 40 m.

Diving among the remains of the old ocean liner that has been resting at the bottom of the Mediterranean for more than a century reminds us of the extraordinary richness of our underwater heritage and provides an intense and unforgettable experience.

To dive here: For your health and safety, it is important that you do not dive when tired or unfit. The use of your own dive computer is mandatory. Gloves, a spotlight, and a knife are recommended. The dive will be planned based on the divers’ experience diving on wrecks.

Certification: Advanced Experienced Diver, TEC45 recommended